As spatial practitioners working with history, culture and heritage, one is often asked to give a three dimensional interpretation of a previous life of a place.

It becomes more challenging the less built fabric one has left to work with – as in the case with District Six – where evidence of place exists mostly in photographs, maps, art, literature and in the memories of old Capetonians.

Furthermore, the act of conserving only the existing built fabric does not always adequately portray the full heritage of a place.

The question that I am posing then is how does one spatialize those aspects of heritage that once formed a significant part of the city’s everyday life?

The work of Lina Bo Bardi presents to us a few lessons of how the many aspects of the past can resonate within the built product. Her work does, however, stem from a bias of bringing to the foreground the intangible characteristics of a place.

1. CAPTURING THE “SPIRIT OF THE PLACE.”

Lina Bo Bardi, an Italian born architect who eventually spent most of her architectural career in Brazil , was commissioned to intervene in the historic core of Salvador de Bahai in 1986. At the time Salvador was proclaimed a World Heritage site by UNESCO because of it being one of the largest collection of 18th and 19th century buildings in the Americas, coupled with its rich and intense slave trade legacy

The scheme that she proposed was aimed at preserving the city’s spirit rather than focusing only on preserving major public institutions. ‘The historic district of Bahia is not about the preservation of important architectures, but about preserving the city’s popular soul’ (Bo Bardi in De Oliviera, 2001:142). Bo Bardi wanted the interventions to contribute to the daily life of its inhabitants as well as commemorating the artistic and cultural legacy – be it contemporary or historic – of the city.

CASA DE BENIN

The project was initiated to commemorate the traditions and culture of many slaves that came from Benin. Pierre Verger, the ethnologist who initiated the project, also wanted it to be an institution where people could study the impacts of slavery in Brazil. The building acts as a living museum of African culture, with a restaurant, gallery, student accommodation and study centre.

The building is situated in a prominent position within the historic core of Salvador. It does not behave like a conventional museum of a storage box for memory. Instead, precious artifacts are displayed much like goods in a shop. This ‘shop front’ character of the museum makes it feel more accessible to the general population and the legacy of the slaves from Benin casually slips into the consciousness of passers by.

CASA DEL OLODUM

This building houses the headquarters of the African Carnival Group. The building is an integral part of the workings of Salvador as it represents an organisation that was essentially borne out a need to combat racism against black people during Carnival in the mid 1970’s. It is also the administrative centre for the unique musical sound that was developed in Salvador during that time – Olodum – an intense group percussion sound. The building houses offices, meeting rooms and a library. It does not have the same free connection with the street as Casa de Benin and its semi-private nature relates back to its administrative purpose.

As much as Casa Del Olodum institutionalizes a contemporary musical culture and Casa De Benin institutionalizes a historic culture, their programme and issue give depth to the built fabric being restored.

2. CRITICALLY SELECTING ARTIFACTS TO CONSERVE.

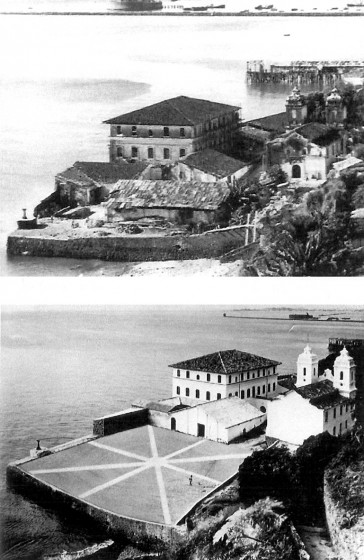

SOLAR DO UNHÃO BAHIA MODERN AND FOLK ART MUSEUM

This compound is situated just outside the historic core of Salvador, illustrates a second idea Bo Bardi pursued: that of critically selecting things from the past in order to make a relevant contemporary space. It was her contention that “the past cannot be repeated and to solve the problems in the present with solutions from the past is an anachronism” (Bo Bardi in De Oliviera, 2001:213).

Before restoration it consisted of a few major building types – warehouse, church, and manor house – and various adjunct agglomerations of buildings. The early 18th century compound has an extensive history of being used as slave quarters, nobleman’s residence, industrial complex, meeting place for political activists, cocoa factory, marine barracks, slum tenement and ruin (De Oliviera, 2001:82).

It is within the realm of these various histories and stories that Bo Bardi never lost sight of the whole, hence, her decision to clear a large part the site and to retain only the church, manor house and some warehouses. This clearing is significant because the gesture is as much an addition as it is a subtraction. It is an addition of an implied order suggested by the landscape whilst it is also a physical subtraction of formal structures.

The landscape becomes the force that starts to unify these buildings as one contemporary piece.

The piazza then, becomes the contemporary insertion that orders an inaccessible past.

3. RUIN AS CELEBRATED.

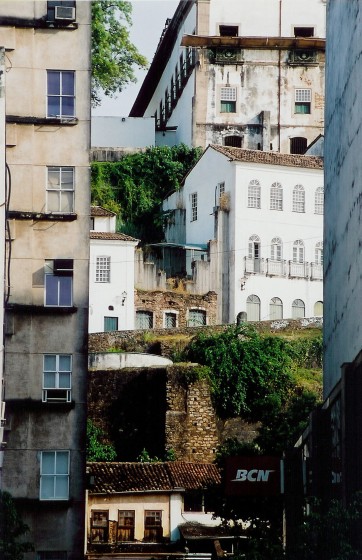

LADEIRA DA MISERICÓRDIA

Guilo Carlo Argan (1901 -1994), an important contributor to theories surrounding restoration, and once mayor of Rome distinguished between two ways of working: conservative restoration and artistic restoration. Conservative restoration sought the replacement of lost elements and the ruin is repaired at all cost. Artistic restoration placed value on the poetic state of the ruin.

In the Misericórdia scheme Bo Bardi worked from Argan’s principle of artistic restoration.

The collection of buildings was all in various states of decay: complete ruin, semi derelict and empty plot. The new intervention tries to mimic the character of the ruin in all its various stages of dilapidation.

The organic shapes of the new restaurant on the empty lot are a direct response to the stone contoured landscape. The surface of the new material reacts similar to light and time as the stone walls. The infill walls are stepped to create a silhouette or profile of decaying structures.

In the previous example subtraction was used as a unifying tool whereas here, the addition of the new material unifies the buildings. This, together with the landscape, indeed captures the essence of ruin.

4. SIGNIFICANCE OF ‘MINOR’ ARCHITECTURE.

The final strategy that Bo Bardi employs in her architecture is the idea of conserving buildings deemed as architecturally insignificant but contributes through other media, like site and programme, to a contemporary cultural heritage. Two examples in São Paulo come to mind – the SESC Pompéia Factory and the Teatro Oficina.

SESC POMPÉIA FACTORY

Bo Bardi was commissioned to design a sports and cultural complex on the outskirts of São Paulo. The site that was identified consisted of a 1940’s factory doomed to be demolished as was common in the area.

The factory held no apparent historic or architectural significance and was, typically, a building designed for labour and production and not enhancing quality of life and lifting the spirit of the people, as the new brief required. In spite of this, Bo Bardi managed to convince the client to keep the building.

By doing this the building is converted from an icon of work to that of leisure. The new programme turns this ‘minor’ insignificant building into a relevant cultural precinct.

TEATRO OFICINA

Newness for the sake of newness, strangeness for the sake of strangeness may attract the eyes but no the intelligence of the heart. (Bo Bardi in De Oliviera 2001:213)

The theatre is situated in Bexiga, an old Italian neighborhood of São Paulo. It was built in the 1920’s as a panel beating shop until the Oficina Theatre group occupied it in 1961.

Bo Bardi converted the building into a 9 m wide by 50 m long box with a ramp like stage running along its length, and a retractable roof. A gigantic banana tree is planted to cover the outside walls and audience members sit on permanent scaffolding erected on the sides of the 9 m wide box. The result is: little differentiation between street and foyer, actors and audience, cloakrooms and stage. The boundaries between the imagination and reality are constantly in flux.

Both these buildings are not pretty in a historic or nostalgic sense. In fact it responds well to the surrounding grit of its time. It challenges conventional notions of what constitute beauty. Finances and architectural effort is spent on elements that enhance character such as the retractable roof in the theatre or the urban boardwalk in the SESC factory project, and little energy is spent on ‘dollying’ up the façade.

Conclusion

Lina Bo Bardi’s work possesses a strong sense of architectural judgment. Formal considerations are borne directly out of the purity of use linked to a wild imagination. Always is the essential character of the project extracted, be it in the past or the present, and formal interventions are made to follow.