In a recent visit to the Groote Schuur Heart Transplant Museum, I saw a large scale photograph of the Rex Trueform Clothing factory, designed by Max Policansky in 1937, covering one wall of the foyer of the museum.

In the photograph, taken in 1967, there is a giant white x marking the spot where Denise Darvall, the donor of the world’s first heart transplant, was struck down by a speedster. The photograph is taken on street level thereby elevating the building to a near heroic quality. I was immediately struck by the formal qualities of the building that the photograph captured – the impressive circular stair enclosed by glass, forming the nexus of where a long, exaggerated and quirky Main Rd façade meets a more mundane Queenspark Street façade.

However, this heroic quality in the photograph is in stark contrast with the reality of its current situation: an empty building parked like a dated cruise-liner on the edges of a magnificent mountain, willing to open its doors to anyone, in a desperate attempt to fill its large expanses of space, which once brimmed with industry.

Indeed, on further investigation, it emerged that the Rex Trueform Clothing factory, once considered as the ‘giant of the clothing manufacturing sector’, has been through multiple transformations over the past 75 years.

Programmatically, it transformed from being the headquarters and showrooms of the manufacturing plant for Rex Trueform in 1937, to being merely the cutting rooms and offloading area in 1948 when a larger, more impressive building was built across the road to house the offices and machinists. Presently there is an uncertainty of its use following on the closure of Rex Trueform’s manufacturing arm in 2006. It continues today empty, except for the Christ Amazing Love Ministries evangelical church, which occupies a small percentage of the building.

Within a limited space, it is impossible to give a full account of the building’s socio-spatial history, but allow me to weave together a patchwork of concerns by making use of my encounters with a few people who were in someway linked to the building.

Manu Herbstein – the nephew, aged 70

I received an unexpected email from Manu Herbstien, novelist and nephew of Max Policansky. He got wind of my activities for the Open House in September 2011, dedicated to the study of Policansky’s oeuvre and he wanted me to take him around a few of his uncle’s buildings.

Not much is written about Policansky and I therefore jumped at the opportunity to meet Manu hoping he would share some insights into Policansky, who is considered by many to be Cape Town’s pioneer modernist architect.

He confirmed some biographical details for me: Max was born in Cape Town in 1909 whose father was a Lithuanian immigrant turned cigarette manufacturer. After a brief stint at UCT, Max went abroad and received his degree in Liverpool. Then, after an extended work study tour of Europe, he returned to Cape Town in 1935 to open up a practice.

With his father and two older brothers’ business connections, Policansky soon received a number of commissions to design industrial buildings – Rex Trueform, formerly Judge Clothing, being one of the first in 1937 and Cavalla Cigarette factory for his brothers Leon and Hymie, next door, following shortly after in 1938.

What emerged out of my discussion with Manu is that at the time that Policanksy produced the core projects of his practice, a period spanning roughly from 1935-1960, the production of modern architecture in Cape Town, was inextricably linked to industry, economy and capitalism, the nature of the resultant buildings being less high art objects as is the case with its European counterparts. Moreover, the modern industrialisation in Cape Town, together with state endorsement, spawned buildings that would ultimately become functionalist testimonies to the manner in which white industry and black labour shaped the social fabric of the city.

Sheila Johnson – the machinist, aged 82

I met Sheila Johnson in her home in Bishops Street, Grassy Park. She worked at Rex Trueform for 20 years from 1953 – 1973. We started the conversation casually first with the establishment of the fact that she knew my late grandmother very well, Eileen Oliver, a factory worker at Park Avenue and later at Monatic. The two, as it turned out were friends, bonds formed at the Good Shepherd Anglican church in Grassy Park where they both worshipped.

She told me that she enjoyed her time working there.

‘The people were nice. I was the machinist there. I was thirteen when I started working in a dressmaking factory in town.

I began to gently probe Sheila about the racial dynamics at Rex Trueform. After all, during the time that Sheila worked there, the mechanisms of state endorsed racism was just being realised. She started five years after the National Party won the general elections in 1948, the Population Registration act of 1950 was just passed and finally the Group Areas act of 1950 was also freshly drafted and approved. Surely this would have infiltrated into the work place?

Repeatedly she said that ‘she liked working there, the girls were nice.’

However, within the context of questions relating to race and discrimination, Sheila started talking about wages. How little it was and how by the time that she gave up her job in the 1970s, the impact it had on her financial circumstance was relatively minor.

Gregory Hoedemaker – the shop steward, aged 50

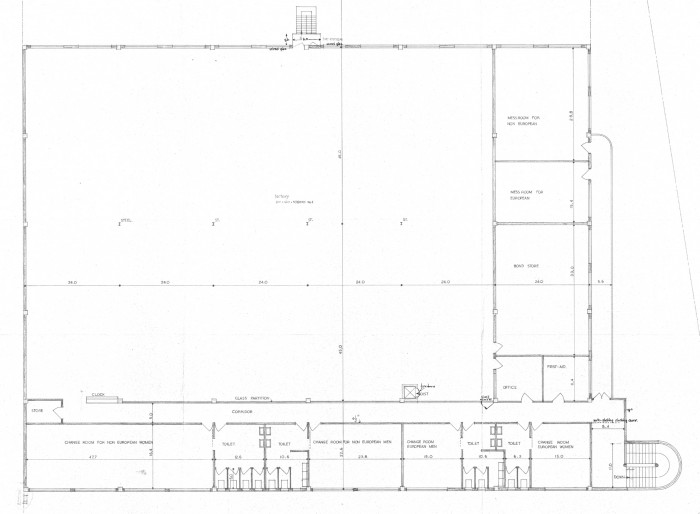

Gregory Hoedemaker, a past shop steward at Rex Trueform, was one of the several players in the mobilising of workers during the strikes in the late 1980s as well as, later during the closure in 2006, negotiating acceptable retrenchment packages on behalf of workers. By the time that he started working at ‘Rex’ the company expanded to incorporate the Cavalla Factory next door, as well as the signature building across the road designed by Andrews and Niegeman in 1948. Gregory took me on a tour of the Policansky building, starting at the corner of Brickfield and Main Rd. He explained that this part of the building was the storage and handling of raw material. Trucks would off load raw material to be laid out and cut in the adjacent cutting rooms. We continued up Brickfield Rd and took a right into Factory Road where you see the back of the building. The façade is just a long stretch of windows to the changing rooms and canteens for workers. It is here in the canteens, he told me, where shop stewards, like himself and Connie September, now a parliamentarian, would address workers and mobilise strike action. As the tour progressed I got a good sense of the intensity of activity that would have transpired during a normal weekday. Trucks going to and fro from the main building to the old, transporting raw unprocessed material to the old building and delivering cut material to be stitched to the main building. I also got a sense that an ordinary work day is seamlessly interwoven with activities pertaining to the struggle for political and economic freedom. Gregory identified, as he talked, the spaces in which power resided – boardrooms, offices, showrooms; and the spaces in which the struggle for power was sought – the worker canteens, security offices and stairwells.

Conclusion

The Rex Trueform factory is currently under utilized and as with all assets the need to develop the building is good business practice to ensure the survival of the company. Agreed. But it is hoped that the development plans would show sensitivity to the fact that the buildings have become representative of a series of key moments in the economic development of Cape Town, the establishment of a black working class and the struggle for political freedom.

As Achille Mbembe says of Johannesburg and referring specifically to its mining industry:

‘It is well known that the city of Johannesburg grew in connection with both forces and relations of production. Less well understood is how relations of race and class determined each other in the production of the city’.

The same could be said of the garment industry in Cape Town. The modern city of Cape Town developed essentially out of an uneven relationship of power between white driven capitalism, supported by the state, and the black working class.

Moreover, the Rex Trueform building, becomes a potential site of redress and renegotiation within the realm of heritage in a post apartheid state.

Herbert, G, ‘Martienssen & the international style, The modern movement in South African architecture’, A.A.Balkema, Cape

Kaplan, M, 1986. Jewish Roots in the South African Economy (Struik)

Mbembe, A, 2004. ‘Aesthetics of Superfluity’, Public Culture 16(3): pp. 373–405, (Duke University Press)

Shorten, J, 1963. The Golden Jubilee of Greater Cape Town 1963 – Cape Town: A record of the Mother City from the earliest days to the present. (Shorten and Smith Pty Ltd)

- Gaelen Pinnock