The project is the refurbishment and repair of an old school building in Greatmore Street, Woodstock. The building is owned by the Western Cape Provincial Government and the University of the Western Cape is investing in the upgrade of the building in order to use it as an arts-based space of higher learning with a programme led by the Centre for Humanities research, a flagship humanities research unit.

Historical background

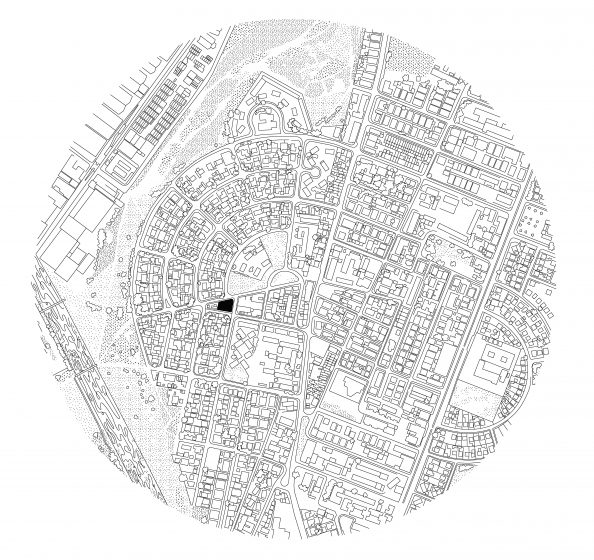

66 Greatmore is located in Woodstock, an area of Cape Town where turn-of the 20th century modern industrial development can be explicitly traced. The rapid growth of modern industry and capital required the implementation of major infrastructural, environmental and social transformation of the landscape. For example, in 1860 the Salt River Railway Works was built, an electrical tram-line was introduced in Victoria Road in 1890, and in 1912 the construction of the Eastern Boulevard (today known as Nelson Mandela Boulevard) and De Waal drive (Philip Kgosana Drive) began. In the 1940s Woodstock beach was reclaimed to accommodate the further growth of urban/industrial development along the railway lines. The implementation of the apartheid legislated Group Areas Act of 1957 saw the surrounding social landscape brutalised by forced removals and separate development of people according to constructions of race.

Parts of Woodstock were designated for those racialised as ‘white’, other parts were designated for groups of people racialised as ‘coloured’ under the Population registration Act of 1951. Although some parts of Woodstock were identified as grey areas, no part of Woodstock was zoned for those racialised as ‘black Africans’.

The school at 66 Greatmore Street was completed in 1916 and emerges as one of the first schools forming part of the 1910 Union of South Africa. It was called the ‘Regent Street School’, named after one of the adjacent streets. According to Sigi Howes, the head of the Wynberg-based Centre for Conservation Education, the Regent Street School is a typical Union of South Africa-era school, and an attempt by that government to provide places of instruction at primary school level for working class citizens. It was strategically located in Woodstock which at the time was experiencing a major industrial transformation and therefore the need for educational facilities for the children of parents who formed part of the new, mainly white working class of the area. The education system was based on Anglo-Victorian ideas of strict separation of activities of play from those of learning; the construction of genders by the separation of boys and girls outside the classrooms; and the extremely didactic styles of teaching. Learners were also closely monitored in an enclosed internal courtyard, and surrounding arched walkways, as well as a large playground overlooked and therefore monitored from classes and offices on the higher levels. The architecture followed this separatist and surveillance based educational ethos by duplicating stairs and entrances according to gender, dividing the playground down the middle with a fence and dividing the lower basement play area into two areas: one for boys and one for girls. The architects McGillivray & Grant Architects designed a building that had a Georgian style yet a modern industrial structure. Drawings dating from 1915 indicates a concrete structure, including a concrete flat roof, yet it made use of ornamental windows with timber frames, stained glass and timber shutters. The courtyard is surrounded by a classical arched walkway and ornate concrete balustrades on the upper walkways. The building was and still is double storey but includes an additionally lower level basement as part of a large playground to the north. The classrooms are of classic and generous proportions and the materiality is warm but resilient. Most of the services were not integrated and a separate toilet block was built further away from the main building.

The area of Woodstock is continually under major societal transformation and when the apartheid government’s Group Areas Act was introduced and implemented between 1957-1965 the school found itself bizarrely located within a ‘white group area’, while across the road, the area was declared a ‘coloured group area’. It was also during this time that the building underwent some major architectural adjustments. The timber louvers were removed, many of the timber sash windows were replaced with steel, the open terraces on roof level were enclosed, a new corrugated roof was added above the concrete roof and its tiled trimmings are removed. There was also more integration of services such as toilets and the large toilet block on the southern end of the site was demolished in.

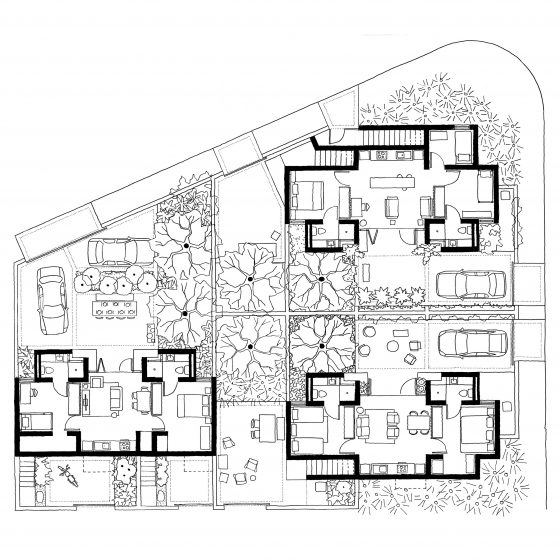

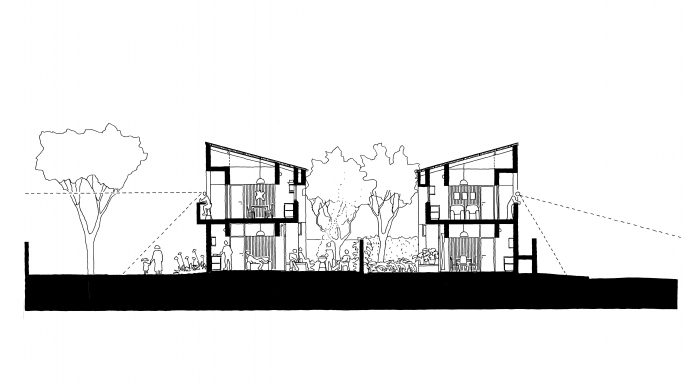

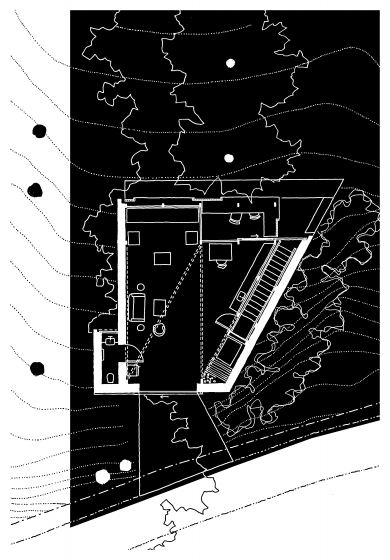

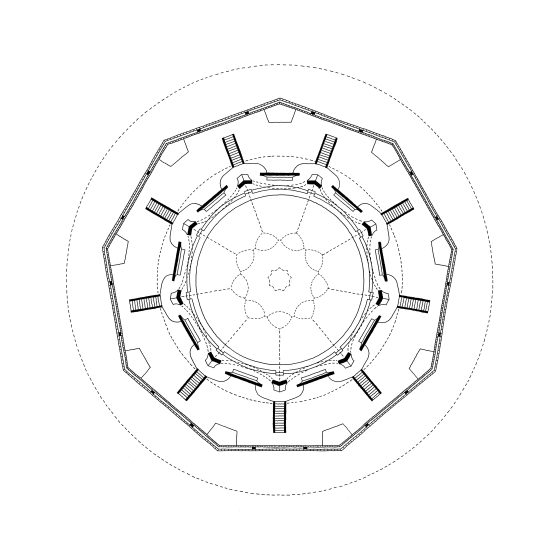

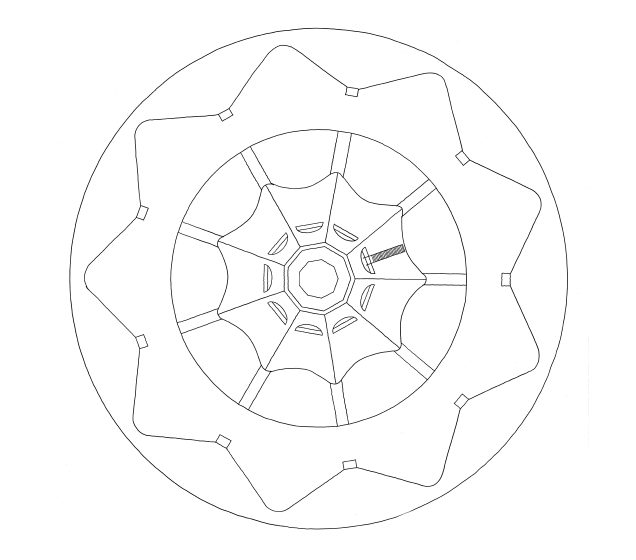

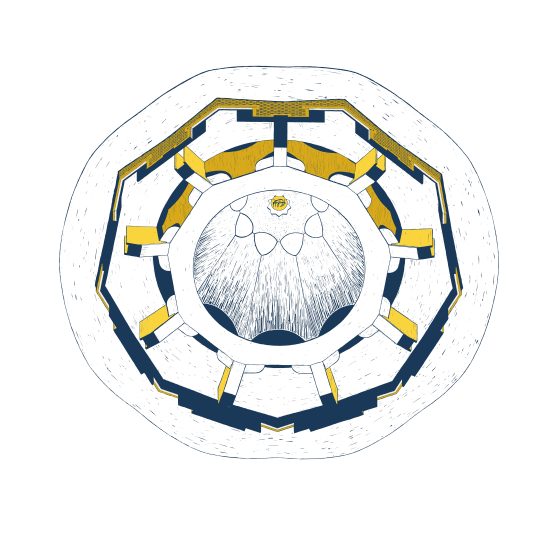

The defining feature of the building is its open courtyard with arched walkway on ground floor and covered walkways on first floor. It is from this walkway that the classrooms surrounding the courtyard, are accessed. The walkway is generous and made of durable and hard-wearing materials. The south wing of classrooms, which faces the mountain, has two levels. The north wing of classrooms, which faces the harbour, has two main levels and a semi-basement level opening onto the playground. The building is placed centrally on an open site. The building functioned as a school for primary school children – ‘The Regent Street School’ – and as an educational facility right up to end of 2015 when it closed its doors.

Heritage Status

The site is located in a City of Cape Town Heritage Protection Overlay Zone (HPOZ) and the building is graded as a 3B heritage resource.

Proposed new work, new function, new approaches

New educational approach

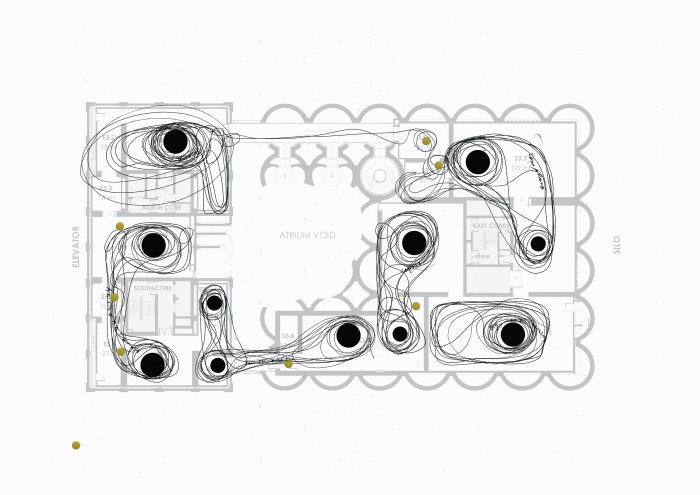

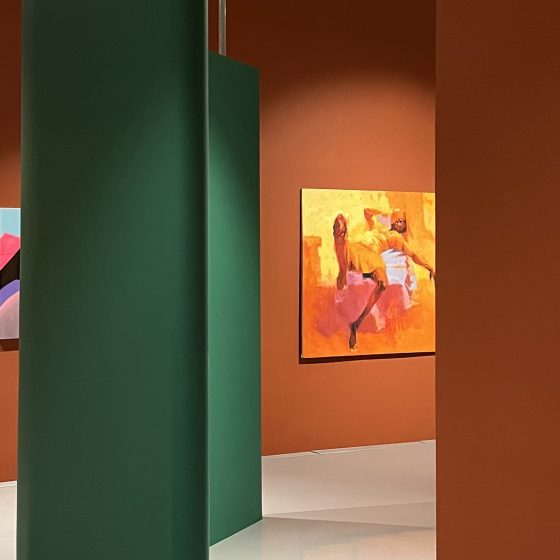

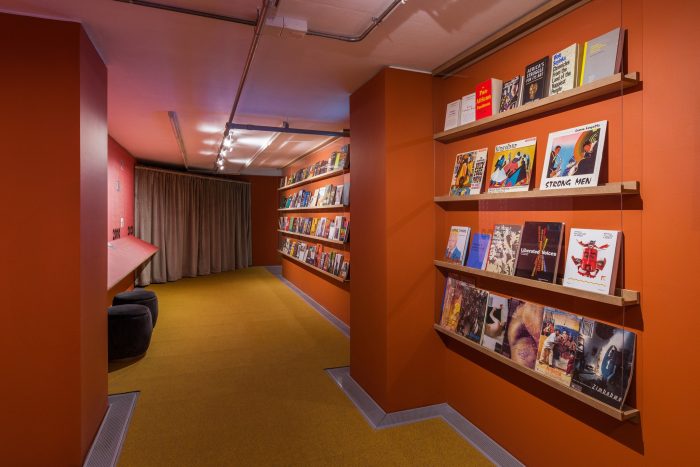

The building is currently under the ownership of Provincial Government but the University of the Western Cape (UWC) has acquired a long term lease to occupy the building. The building is specifically been acquired by UWC for the use as arts based education for the Centre for Humanities Research (CHR), which includes, workshop areas, film and music studios as well as seminar spaces. The UWC/CHR has since its inception, been concerned with the connection between the humanities scholarship and the production of arts practices and the role it has to play in the production of new conceptions of social cohesion and anti-racism. As a historic black University, the agenda of social redress and collective work towards rebuilding society as antidote to racist regimes, is not new for UWC. While the function of the building will remain the same (education) the register will be distinctly different. Students will be encouraged to learn through play and experimentation, strict societal divides are explicitly challenged, and freedom to think and explore is the main driver of the CHR’s educational mandate.

New architectural features

The existing tall volumes, robust structure and open space make it ideal for the activities linked to the UWC/CHR but in certain areas the architecture must be adjusted to follow to suit and to adhere to contemporary building regulations. Overall, we would fit out and furnish the rooms to meet the standards of UWC. We also aim to refurbish and maintain the building to make it suitable and safe for use, since the building is in disrepair in many parts. In short, the heritage proposal is a conservation approach whereby the restoration of the building is largely in balance of the practical needs of the users and new building regulations.

New circulation core, lobby and lowered basement floor

The character of the building would remain largely untouched yet the main changes will occur along one of the circulation cores where there is a requirement for an elevator for universal access and a wider escape route and stairs. At the basement level we are proposing to fit out a workshop and this requires that the floor to ceiling must be increased as it currently does not comply. Because of this, some adjustments to the elevation would then be foreseeable.

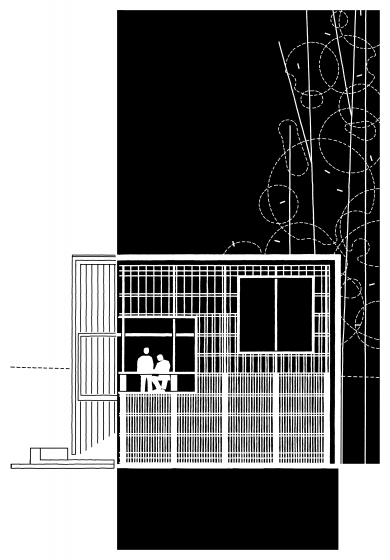

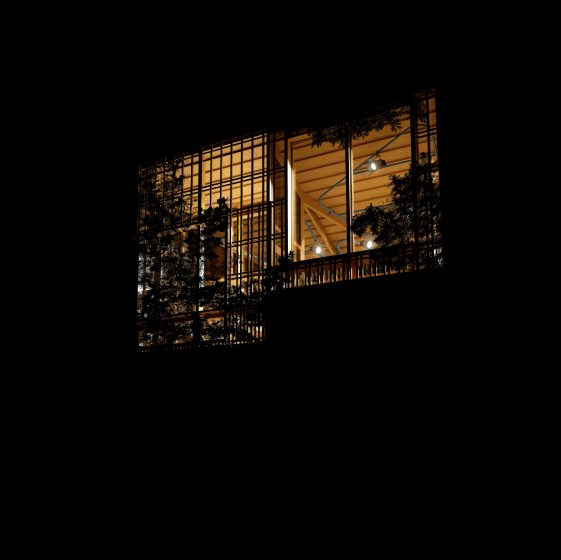

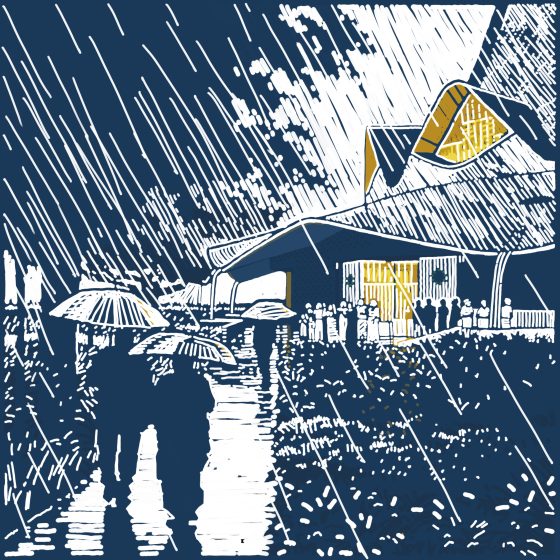

New roof over courtyard

The courtyard presents an opportunity for UWC/CHR to organise large gatherings. We propose to cover the courtyard to protect it from wind and rain yet leave the sides open to allow proper ventilation of the space. The design, as illustrated in the amended drawings, is sensitive to the heritage resource in that it is not visible from the outside. From inside the courtyard roof is placed at the highest possible level, in order to maintain a sense of height and volume required of an institutional building. The high transparency level of the glass conserves the light quality of the space whilst maintaining responsible UV levels of the space.

New window frames and glazing

Most of the original timber frame windows have been replaced with steel frames during a 1960s maintenance upgrade. The windows facing Greatmore Street are the only remaining timber frame windows. For optimum climate and acoustic control we propose that all the steel frame windows be replaced with custom aluminium frames and new glazing. The timber frame windows on Greatmore Street would be repaired and reglazed as timber frames.

Ethical redevelopment

We are aware that 66 Greatmore is located within a historically and contemporary highly contested area regarding re-use of buildings and public spaces. We as a team, acknowledge that large parts of the Woodstock/Salt River area is under pressure from being transformed into privatised worlds of disintegrated economies and people. Our approach is that the 66 Greatmore project intervention should be an antidote to crude developments in the area, which causes homogenising of neighbourhoods and reverses some of the progress made in the democratic society. We have engaged with the principles of Ethical Redevelopment as outlined by artist and activist Theaster Gates as well as ideas around Repair as proposed by the artist Kader Attia as it applies to colonial and apartheid spatial history. We have also co-produced the architectural language and interventions around the ethics of the CHR and in conversation with scholars like Premesh Lalu, Heidi Grunebaum and others.

Relevant spatial frameworks

Our approach is also, to embed any work to 66 Greatmore within the Woodstock/ Salt River revitalisation framework as prepared by NM Associates Planners and Designers, dating from 2002. This document calls for sensitive reuse of heritage resources with particular emphasis on the upgrade of public spaces. 66 Greatmore is a publicly owned building with public investment (UWC) and its upgrade, spatial development as an arts-based educational facility for UWC would be in the interest of not only Woodstock communities, but of the metropole as whole.

It is for this reason that the heritage significance of the building covers a broad spectrum of related issues: social, technical and aesthetic and that respectful, mindful interventions should take cognisance of these overlaps. It does not necessarily propose that the aesthetics of the building be reinstated to the original state by, for instance including the original tiled roof areas, timber framed windows or concrete flat roof.

Our approach is based on an assessment of the existing building and proposes that the new users adjust their needs to fit the existing building and the site. No new structures are proposed on the site or as additions to the buildings, however we do propose a roof over the existing courtyard. The roof over the courtyard would allow maximum all-weather use of the space for the University and would be designed that it respects the character of the internal space and that it would not be visible from the street. Alteration of the existing fabric will largely revolve around meeting modern accessibility standards, meeting practical needs and rehabilitating built fabric.

Conclusion

The significance of the building and site lies in the fact that it served as an educational facility for its entire lifespan. It was constructed as one of the first Union Government Schools in the Western Cape. The architecture followed the Anglo-Victorian education ideology of separating genders; work from play; and allowing for strict surveillance of learners by teaches. The design followed classical proportions and decorum. Societal changes saw the demographics of the area engineered and also, again design changes ensued. The building experienced major changes in the 1960’s which neutralised the building’s character. The courtyard, the internal volumes and the access to open space and views is a significant heritage feature of the building, so too is its programmatic feature as an educational facility. With its overall neglect, haphazard use over the recent years, thus too, the significance of the building shifted and we are now, with its new potential occupation by UWC, on the precipice of a significant moment for the site and the building. Our intervention does not propose a change in the historic use of the building but it does propose that the circulation be altered to adhere to the progressive educational attitudes of UWC, as well as the requirement for universal wheelchair access. To make the courtyard more usable in all weathers we propose a roof. In order for the basement to comply, we propose a lowering of the floor areas and the concomitant changes to the elevation. An overall upgrade of the building regarding the repair of damaged areas is proposed, although we do not propose returning the building to its original form. In essence the design is a consequence of a thoughtful, ethical and collaborative process in order for UWC CHR, in partnership with Provincial Government, to do the important work of social cohesion through arts based higher education.

Lightness

Lightness