Wolff Architects were appointed for the design and technical documentation of this temple following an international competition. The Bahà’i International Office for Temples and Sites appointed Rankin Engineering in Lusaka as commissioning client, contractor and civil, electrical and mechanical engineers. The bulk of the architectural work was done during the Covid19 lockdown.

The Bahá’í faith and its temples

The Bahá’í faith is a religion founded in the 19th Century in Iran and has spread throughout the world since then. The faith was established by Bahá’u’lláh and his letters and epistles; along with thesem are works of the Báb, his forerunner, and writings and talks of his son, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. These works have been assembled into the Bahá’í scriptures.

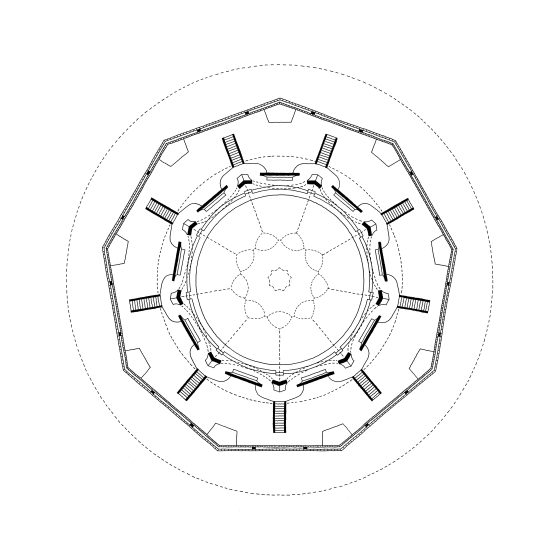

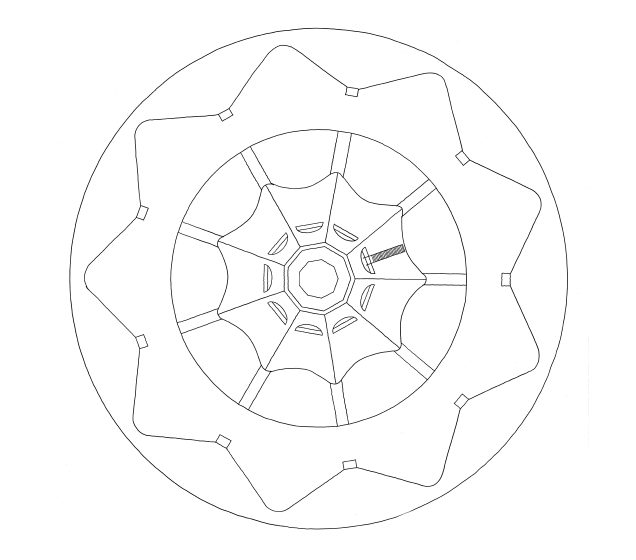

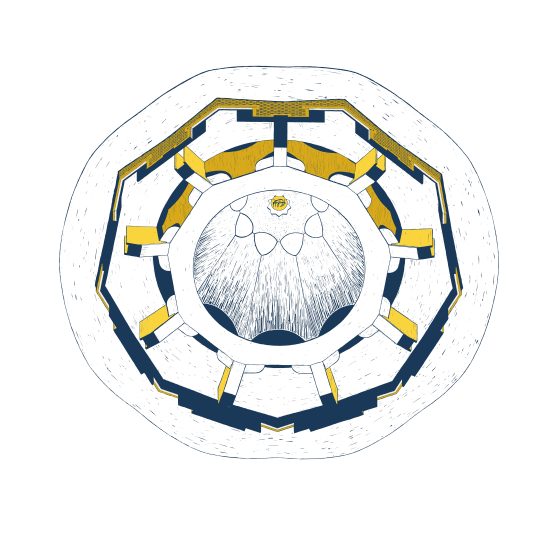

The Bahá’í faith stresses the unity of all people as its core teaching, and temples are required to be an expression of the commitment to equality. All temples should be nonagonal (nine sided) in plan and should be formed by a repetition of nine, identical segments, around a central dome. Each segment should have a door, with no one door being more important than the other. This arrangement of the space and entry points is meant to show that people from everywhere are welcomed equally. The temple should reflect local traditions and should be built by people from the surrounding area. The temple should be “as perfect as possible” and must be brought about through a process of collaboration and joint decision making. The seating inside the temple must face Qiblih, the direction that Bahá’í should face when saying their daily prayers.

Six continental Bahá’í temples have been built as symbolic, continental centres of assembly. This temple in Kinshasa is one of a series of National temples which serve as a daily space of prayer and devotion, and also as a national space of assembly on significant days in the Bahá’í calendar. The national and continental temples are always set in expansive garden settings, which are open to the public and are meant as spaces of meditation and reflection. These tranquil gardens should have the temple at its centre.

The National Bahá’í temple of the DRC

The site for the temple is just off Avenue Patrice Lumumba, the main road running through Kinshasa. Most of the site is a level plateau adjacent to a fertile valley. The temple is sited on the cusp of the plateau, overlooking the valley with views of the Congo River in the distance. A nine sided star marks the periphery of the garden, but instead of its “perfection” being imposed on the landscape, the characteristics of the topography are allowed to enrich the experience of traversing these pathways around the temple.

Lightness

Lightness

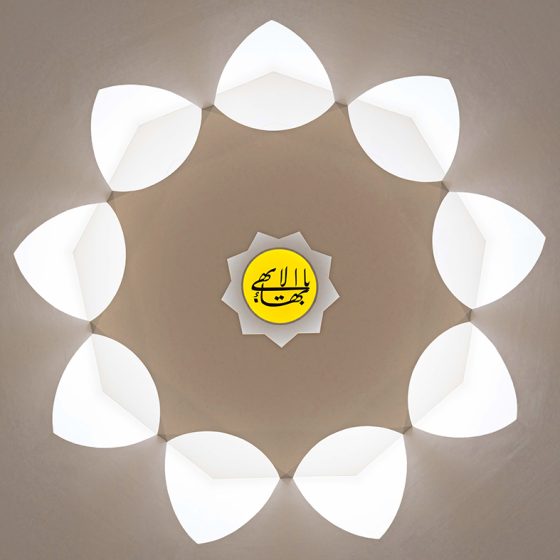

A sense of the sacred is evoked in this temple by making the structure miraculously light. The central dome rests on a thin, hovering slab with no columns supporting it. All structural edges are super thin (125mm) and are evidently too light to support the structure they carry. The enactment of an effortless lightness becomes an allegory of the sacred.

This is technically achieved by revealing secondary structure, whilst concealing primary structure; the structure of the dome rests on the gallery which conceals a compression ring in the tiered seat, yet all the gallery slab edges are thin. The centroid of the dome structure coincides with the centroid of the compression ring and the centroid of the stairs. Although the stair stringers are thin, the change in level around the stairs conceal a deep stair arm, capable of carrying the forces. The stairs support the hovering gallery slab, whilst the structural system is held together by an underground tension ring.

The edges of all openings in the crown of the dome and the external skin of the building is also 125mm thick which gives the sense of a cut through a delicate membrane.

Light

A great deal of time was spent during the design process to establish the character of the light. The search for an authenticity in the light was resolved by not relating the character of light to expressions typical of other religions, such as high glare light of stained glass windows in churches or the “pixelated” light panels in screens of mosques. The desire for expressions of equality in the religion informed the decision to create low glare light that will illuminate the interior in an equivalent manner. This character of light illuminates all the spaces occupied by people. The light in the dome works somewhat differently; light from outside illuminates the exterior dome at the top of the building and this light enters the temple through nine openings, cut into the crown of the inner dome. The dramatic contract between the light levels on the two domes allow for very simple and cost effective dome construction. At the centre of the temple is a nine sided star with the “Greatest Name” (name of God) inscribed on a translucent panel.

Art

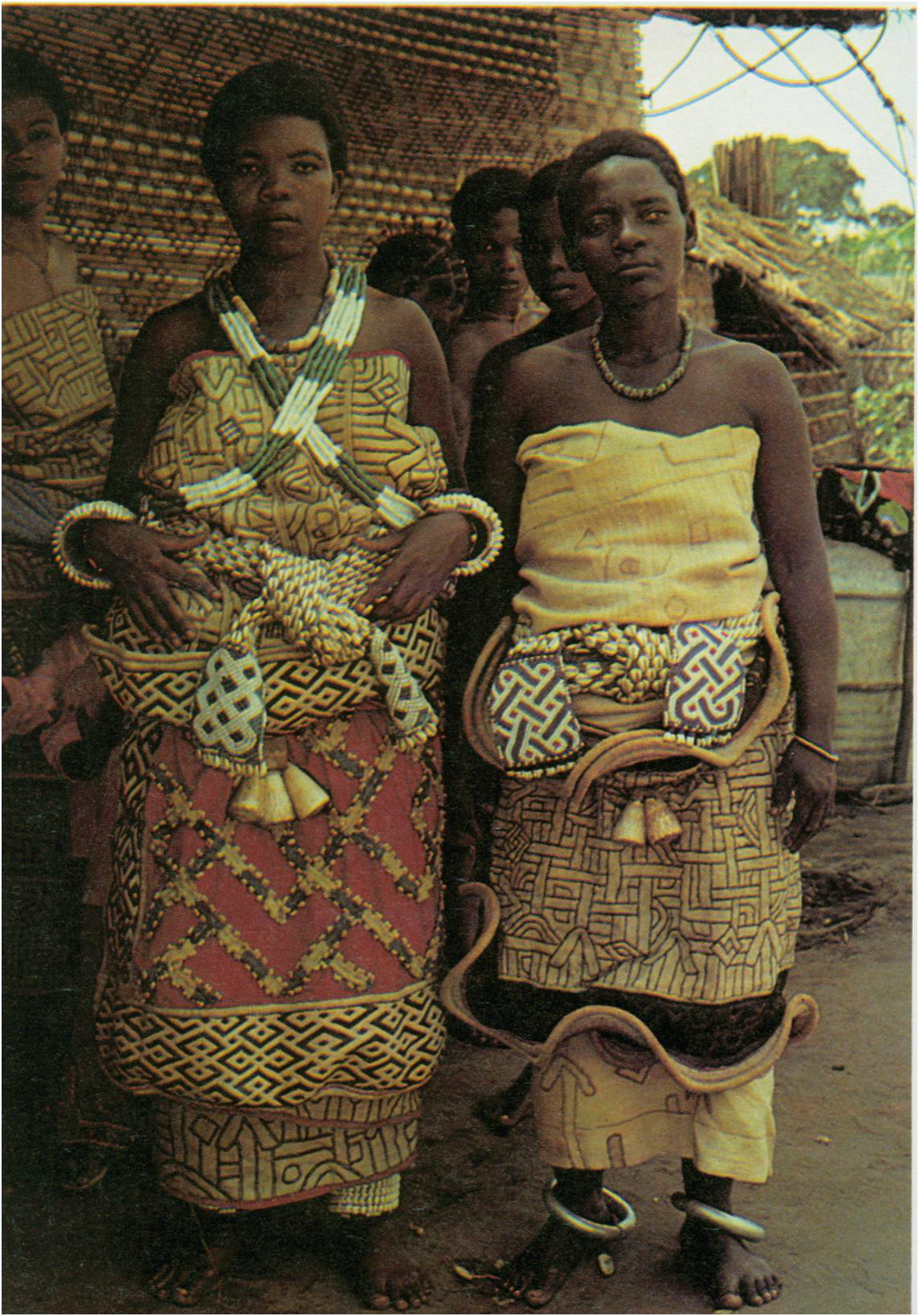

Textile art is a persistently extraordinary art form in the DRC. In studying historic textiles of the country and discussing the appreciation that people have for contemporary textile art, several expressive possibilities emerged. Firstly, that many textiles are produced collaboratively; for instance the back of a textile would be woven by men and the embroidery on the front would be made by groups of woman who work in the tradition of pattern making. The final textile surface is an assemblage of portions made by different individuals. Correspondences are sought in the patterns of adjoining panels during assembly, but mismatches are also treasured. Secondly, in softening the textile through pounding, sometimes the surface is broken. The broken areas are patched and these marks of repair are integral to the new piece. Repair becomes part of creation and the ongoing life of the textile. Thirdly, Congolese textiles are not made to be in museums as flattened out pieces on display. The ideal way of appreciating Kuba or Shoowa textile for instance, is to see it wrapped around a body, in motion. Patterns should be appreciated on an undulating surface.

The artwork for the exterior of the temple was the result of a collaborative design process. Wolff Architects collaborated with Maja Marx to establish the design which was then passed on to the Bahá’í congregation of the DRC and the international office to comment on and propose alternatives. The final design was established through several iterations and was finally accepted by all involved.

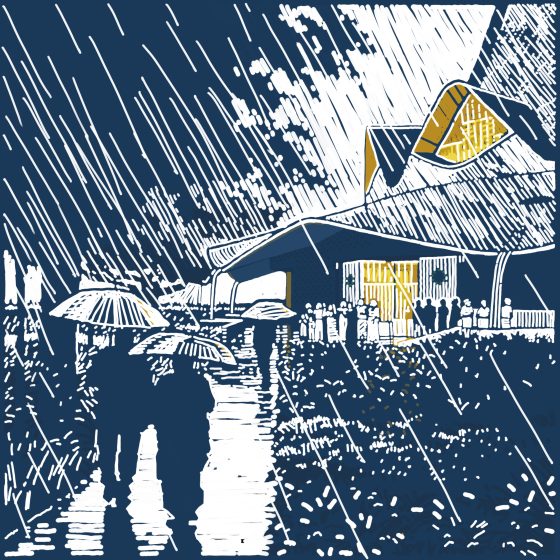

As much as the exterior surface relates to the textile traditions of the DRC, it equally makes reference to Bahá’í scriptures; the metaphor of rain is used to explain how God’s grace is bestowed equally on all people. The importance of the collective is reinforced by statements such as “We are drops of one ocean, waves of one sea, flowers of one garden and leaves of one tree.” The idea emerged that a correspondence exists between these Bahá’í images and people’s daily experience of thunderstorms and the sense that the DRC, as a country, is defined by being the basin of the Congo River.

The tessellated ceramic tile surface covers the temple form like a textile wrap. The logic of tiling lent itself naturally to the language of weaving. The sense of a delicate covering is enhanced by making the surface pattern independent from the building form that it is applied to. The surface pattern was established by flattening the curvilinear surfaces into a series of canvases onto which the pattern was painted. The art was then converted into pixilated colour accent segments with contrasting matt and gloss finishes, which were manually applied. The 135 000 tiles were then reduced to 22 500 sets of individual tiling instructions which were carefully applied by Congolese tilers.