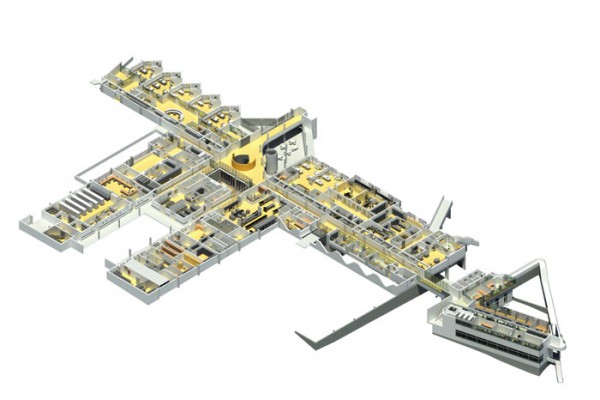

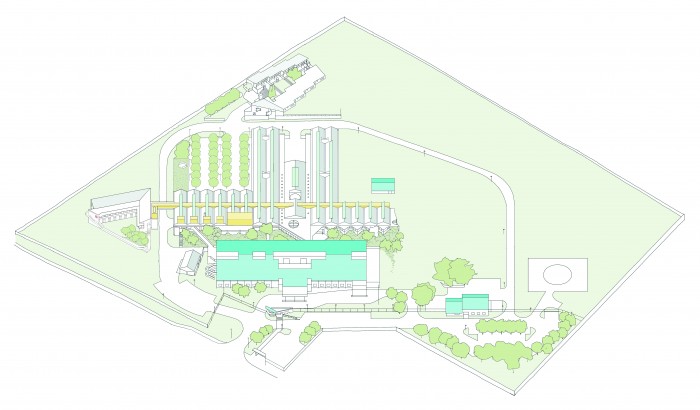

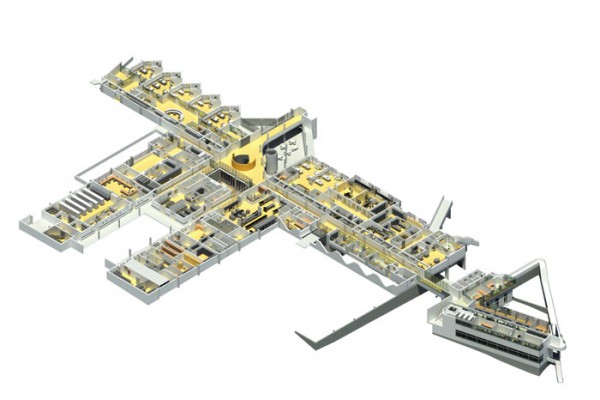

The work that Wolff Architects have undertaken at the Vredenburg Hospital is a major addition to an existing provincial hospital. The existing building contained several wards and significantly, the public entrance. The new extension contains the paediatric ward, theatres, support services (kitchen, workshops, laundry, etc), psychiatric ward and the administration offices.

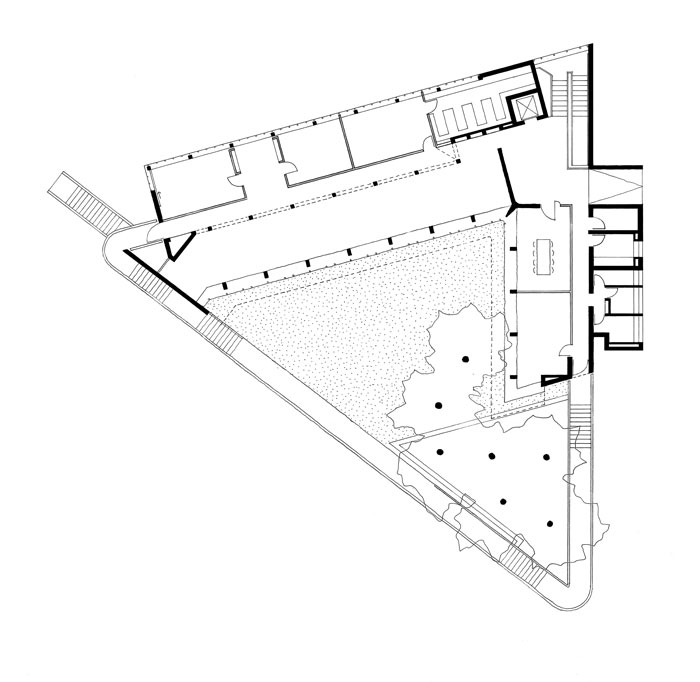

Administration building

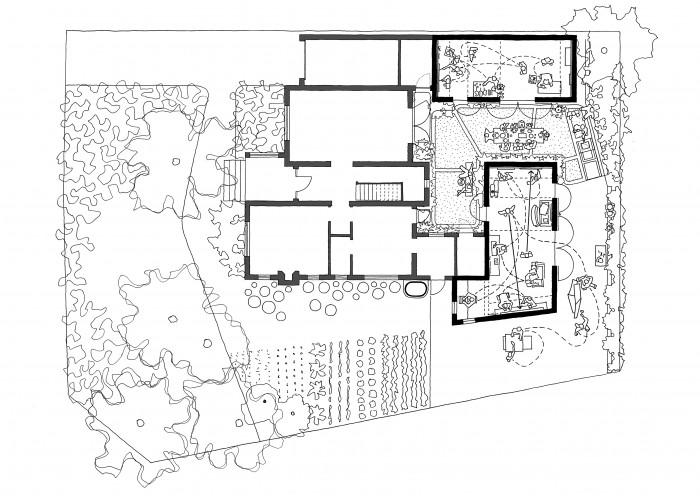

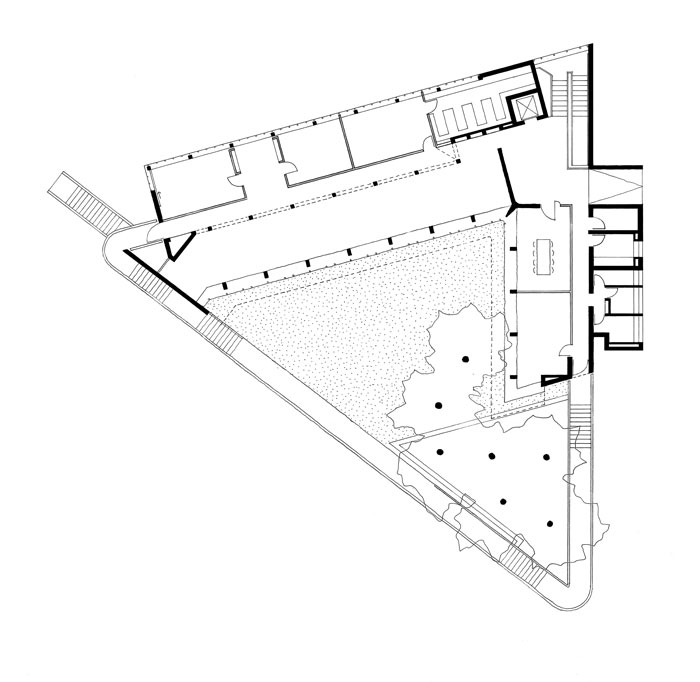

The administration building is entered on the upper floor, via a bridge, over the ring road. From the upper level one can descend to the lower level of offices which face onto a garden. The triangular garden has one open side which faces the town centre. A low wall removes the middle ground from the town view which in turn is bound by two fire escapes ascending to the upper floor.

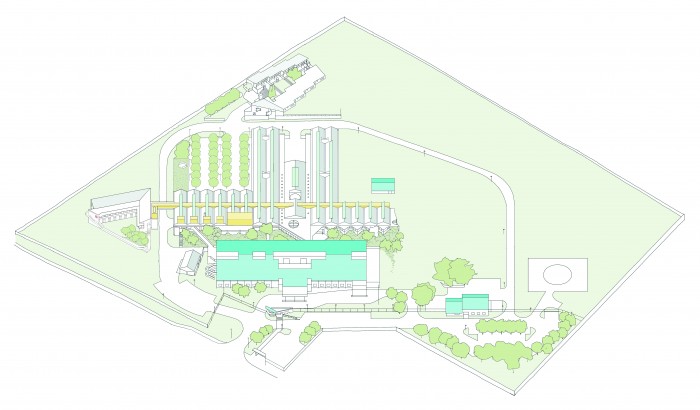

Site order

A ring road was introduced to order activities and open space on the site. This ordering device was used to move the hospital campus from a sub-urban arrangement to a more urban arrangement. Buildings could be placed on either side of this road and a series of defined outdoor spaces could be made with views to the distant mountains. Through terracing of the outdoor spaces, the hilltop location of the site is exaggerated.

The architectural project focussed on two primary objectives; a naturally lit interior and the development of a super-form and a sub-form.

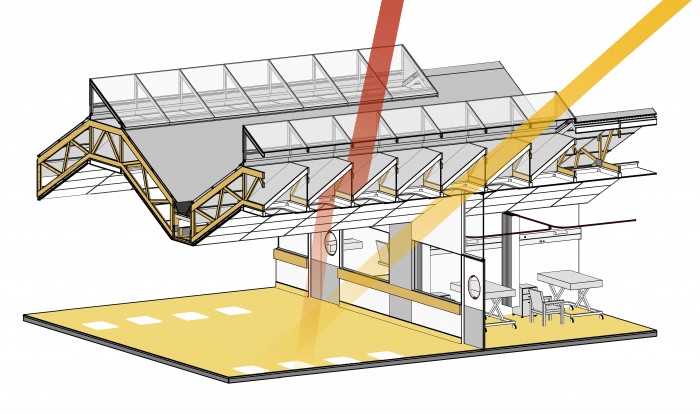

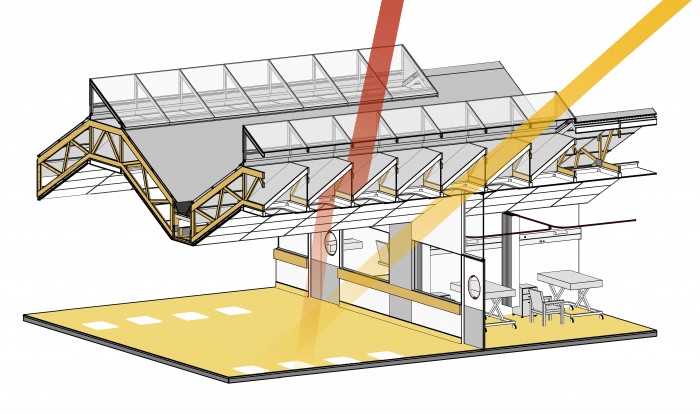

Naturally lit interiors

To have the interior of a hospital naturally lit sounds simple enough, but it is often only partially achieved. Conventionally, the demand for deep floor plans and ceiling based MEP services mean that the floor plates of a hospital are overshadowed by a layer of services which is impenetrable to light. Light is usually admitted from the facade into the wards which leaves the depth of the plan, where the staff are often located, artificially lit. Often, primary service runs are located in the ceilings above corridors and therefore they are devoid of natural light.

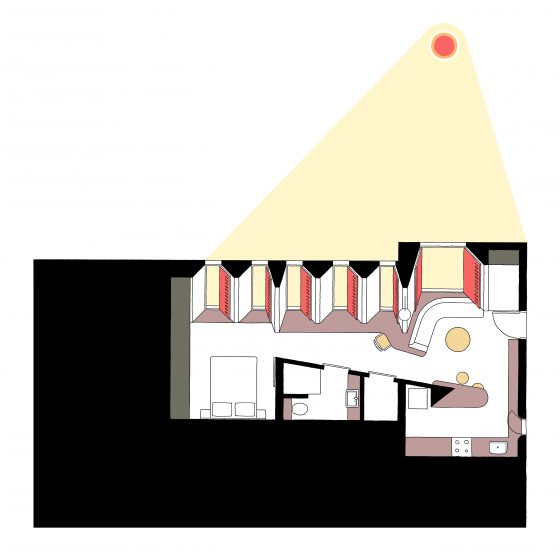

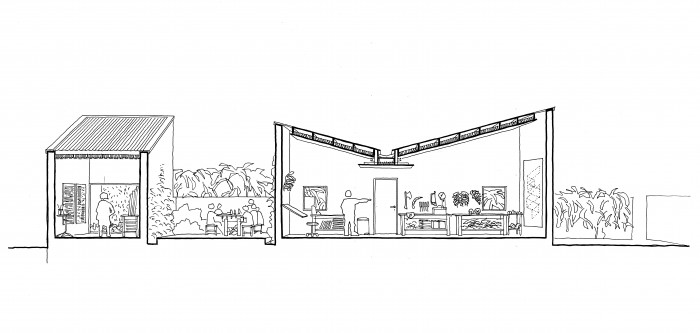

In this design, all habitable spaces are located on the upper floor, and therefore the opportunity existed to have the entire floor plate naturally lit. This was achieved through “combing” the MEP services into a pattern that would allow light to enter between service runs. A primary service corridor was developed on top of a line of service rooms (ablutions, storerooms, sluice rooms, etc) and adjacent to the primary circulation corridor. This move allowed the corridors to be naturally lit whilst having an easily accessible service corridor. From the service corridor, the MEP services branch off perpendicularly which allows roof lights to be located parallel to the service runs.

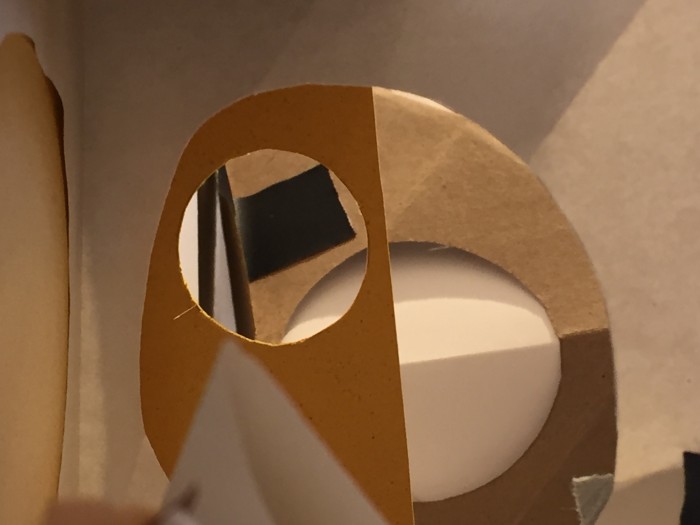

The roof lights were designed to separate light and heat. The roof lights have reflective baffles inside them which allows direct sunlight through in winter, but only reflected light in summer. The outer layer of glass encloses a ventilated void which allows heat to escape.

The design of the roof lights allow the hospital to have a 80% daylight autonomy.

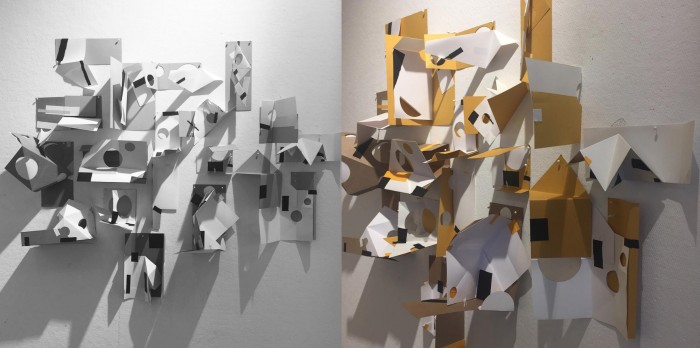

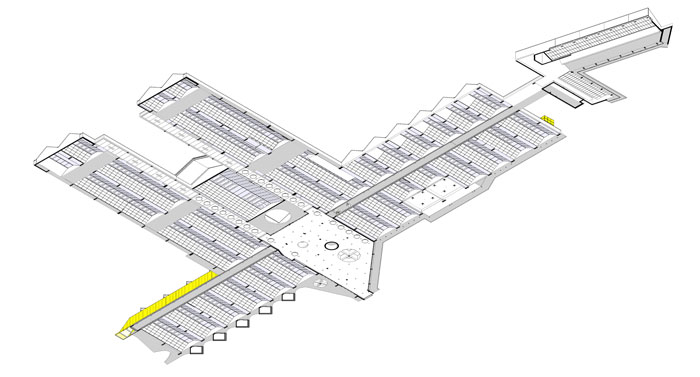

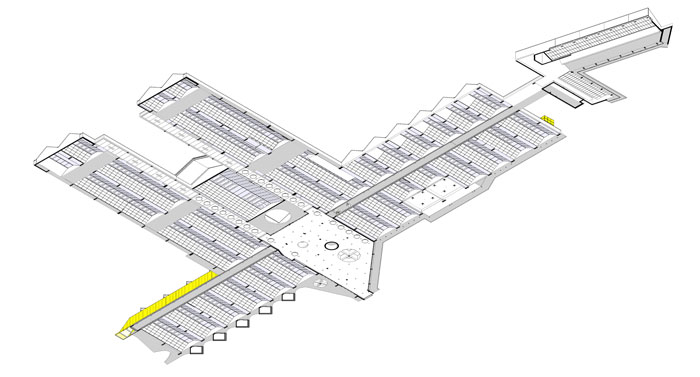

Super-form and sub-form

The architecture of hospitals is often overpowered by technical and functional demands. To make matters worse, changes to the fabric and the services over time, systematically removes any architectural quality from the original building by attrition. To allow for adjustment over time, the additions to the Vredenburg Hospital were designed as two autonomous architectural systems: a super-form and a sub-form. The super-form is the physical framework which sets up primary relationships with the city, the outdoor spatial system, with light and the large scale circulation through the building. The super-form is the most permanent part of the building and in this case is achieved through a normative construction system, The sub-form is the plethora of cellular rooms, all of which could be changed without any substantial effect on the super-form.

In this hospital, the super-form takes the form of an autonomous roof. Substantial inspiration was drawn from the way sub-urban shopping malls are constructed; a single roofing system over the entire plan with the only fixes being the points, where light enters the plan. The plan form becomes changeable but the quality and pattern of light are non-negotiable. The roof is shaped as a series of undulating bays, the size of which corresponds with a typical ward width. The roof lights are in the centre of each bay. When primary access doors are located under the roof light and service doors are located away from the primary light points then spaces with multiple doors become much more readable; the roof establishes a plan order below it. The normative construction system achieves lower construction costs and in its repetition makes for a consistent manner in which MEP services are located within the plan and the section of the roof.

The super-form establishes a consistent architectural language over the entire plan; the surgeons have the same space as the cleaners. This consistent architectural treatment is fundamental in a society where the unequal treatment of people has been entrenched over centuries and architecture been deeply complicit in maintaining such inequality.